In this scenario a naive reporter’s early success with a government minister leads to an ethical dilemma when a ‘favour’ is demanded in return.

A young journalist is appointed as a parliamentary reporter for a public service broadcaster in a Western democracy.

He is assigned to cover a specific region of the country. His job is to get to know his area’s MPs (members of parliament) and to cover their activities.

Keen to make an impression, he draws up a list of all the politicians on his new patch. His region has several constituencies where the sitting MP is a senior government minister.

A national story breaks. The minister in charge of the department concerned is on the reporter’s list. The journalist makes contact.

The minister, a Secretary of State in the department at the centre of the story, invites the reporter round to his private rooms in the parliament building. He has, so far, been refusing to be interviewed on the topic.

They have a chat, the reporter explains that he has taken over the patch and that he wanted to get to know all his MPs.

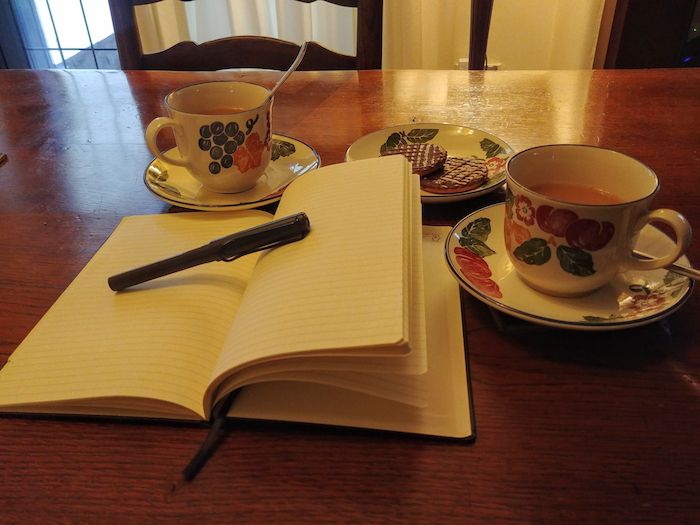

The minister seems friendly. He offers the reporter a cup of tea. They appear to get on well. The MP’s assistant is hovering in the background.

Towards the end of the chat the reporter asks the politician whether he would agree to a short recorded interview on the developing story. He says yes.

An audio clip from the interview makes national news. After it is broadcast, the reporter’s boss praises him for his work; it’s a good start in the new job.

Three months later the minister’s assistant calls to tell the reporter that the minister has a story for him. The reporter is excited. It sounds like he could be in line for another scoop.

He’s invited to visit the MP’s office again. When he turns up he’s handed a piece of paper. He reads what seems like nothing more than a public relations plug for the minister; the reporter fails to see the story.

He questions whether there is anything newsworthy to report. The minister seems surprised, and replies that he had done him a favour with a quote three months earlier and now it’s his turn to return the favour and report what the minister wants.

The reporter had no idea that the minister would want to call in a favour after giving a quote.

The minister’s assistant talks to the reporter as he leaves and suggests that it might not be as easy for her to arrange a meeting in the future if the reporter fails to cover the story the minister wants publicised.

What should the reporter do?

a) Do the story the way the minister wants. The reporter will be covering the region for some time, and he does not want to fall out with one of the most senior politicians on his patch – doing so could mean that he will miss out on quotes in the future when he might need them.

b) Ignore the request, knowing that he is under no obligation to cover the story. He might have been naive in the way he approached the first meeting with the minister, but he didn’t do any deals to get the first interview.

The suggested approach

Political interviewing should never be a matter of returning assumed favours.

Journalists should never do deals to get information or interviews. There will always be a price to pay if they do.

In this case the journalist reported the matter to his line manager who also failed to see the news story in the issue the minister wanted to publicise. And, even if he had, it would have been wrong for the story to be covered on the understanding that it was because a favour was being returned.

Interestingly, deciding not to cover what was a PR stunt didn’t disadvantage the reporter when it came to requesting future interviews. The politician was clearly trying to exploit the situation.

Summing up

A young parliamentary reporter, eager to impress, secures a crucial interview with a senior minister by establishing rapport. However, months later, the minister attempts to leverage this initial interview into a reciprocal favour, demanding positive coverage of a non-newsworthy public relations (PR) piece, implicitly threatening future access if the reporter refuses. The reporter, realising the minister’s attempt to manipulate him, consults his manager. They decide to reject the request, upholding journalistic integrity and demonstrating that ethical reporting doesn’t preclude future access.

Analysis

- The setup: A young, ambitious journalist gains early success by securing a crucial interview with a senior government minister. This success stems from the journalist’s proactive approach and the minister’s willingness to engage.

- The ethical trap: The minister later attempts to leverage this initial interaction, demanding favourable coverage of a non-newsworthy PR piece as a “returned favour.” This creates an ethical dilemma for the journalist, who feels pressured to comply to maintain access and avoid jeopardising his career.

- The core issue: The scenario highlights the potential for political figures to exploit the naivety and ambition of journalists, attempting to blur the lines between professional interaction and quid pro quo arrangements.

- The resolution: The suggested approach rightly emphasises journalistic integrity. The reporter should refuse to comply with the minister’s demand, and the line manager should support this decision. The outcome demonstrates that ethical journalism doesn’t necessarily lead to professional disadvantage.

- Understanding the power dynamics:

- This scenario reveals the subtle power dynamics at play between politicians and journalists. Ministers often control access to information, creating a potential for manipulation.

- It underscores the importance of journalists maintaining independence and avoiding situations that could compromise their objectivity.

- The importance of clear boundaries:

- The reporter’s initial friendly approach, while well-intentioned, may have contributed to the minister’s perception of a reciprocal relationship.

- Journalists must establish clear professional boundaries from the outset, ensuring that interactions are based on mutual respect and the pursuit of accurate information, not personal favours.

- The value of editorial support:

- The line manager’s support is crucial in reinforcing ethical standards and protecting journalists from undue pressure.

- Strong editorial leadership is essential for maintaining journalistic integrity and ensuring that news coverage is not influenced by political agendas.

- Long-term vs. short-term gains:

- The temptation to comply with the minister’s request might offer short-term benefits, such as continued access.

- However, compromising journalistic ethics can damage credibility and lead to long-term professional consequences.

- The long term benefit of keeping ones integrity is far greater than the short term gain of a story.

- Recognising manipulation:

- The ministers assistant using language that implies a loss of access, is a form of manipulation. Recognising this is a key skill for a journalist.

- Building a robust network:

- While this minister was trying to manipulate the reporter, by maintaining a professional and ethical stance, the reporter has shown that they can not be manipulated. This builds a reputation of integrity, and in the long run will help the reporter build a robust network of reliable sources.

Key takeaway:

This scenario serves as a cautionary tale for aspiring journalists, emphasising the importance of ethical awareness, professional boundaries, and editorial support. It highlights the need to prioritise journalistic integrity over short-term gains and to recognise and resist attempts at manipulation.

Related training modules