In this scenario we look at how a journalist should act when they witness a tragedy unfolding and have to decide whether to help, or to stand by and report.

The scenario also looks at how senior editorial managers could, and probably should, support their journalists working in difficult conditions.

Becoming part of the story

Imagine you are a local radio news reporter working in a city whose football team has qualified for the 1985 European Cup final (later renamed the Champions League).

Your editor holds a planning meeting a month before the game. Three sports reporters are sent to provide commentary and gather interviews, while you are assigned to cover the news angles.

The brief is to travel with the fans, stay with them in the city where the match is being played, mingle with them at all times, and file regular reports on the atmosphere before, during and after the game.

You are also asked to gather enough material in order to produce a half-hour documentary to be broadcast in the station’s news and current affairs programme a week after the game.

You arrive in the European capital, where the game is being staged, a day early to soak up the atmosphere.

On the morning of the game, the fans invite you to join in a football match with the opposition fans in the street close to the stadium. The fans are enjoying themselves.

You record some of the atmosphere and a short piece for your programme. Mobile phones were not common in 1985 so you need to find a telephone box to send a 40-second news report on the build-up to the match.

You find a phone, dismantle the mouthpiece, attach two crocodile clips to the wires, and plug in your Uher reel-to-reel recorder to transmit your material.

At 4pm the police usher the fans into the stadium – more than three hours before the kick-off.

It’s cramped, the stadium is in a poor state. The concrete terracing is crumbling. The barriers are unsafe.

The fans become bored. Fireworks are thrown. They start to taunt each other either side of a thin wire fence separating the two sets of supporters. It starts to buckle under the pressure.

The police move in. Some in the crowd try to escape, others surge forward. The fence collapses, then a wall. Fans are crushed under the weight of the concrete. You hear screaming.

Many fans are trying to exit the terracing as more police arrive. You pass the wall which has fallen. Fans from both teams are trying to dig people out of the rubble. Some beckon to you to help them.

What should you do?

- Help those who are trying to rescue the injured fans.

- Try to capture some of the noise for your programme and record a situation report.

- Keep moving, you need to find a telephone box in order to contact the news desk.

Suggested response

Reporters are often caught up in events. Most of the time we are just witnesses to incidents which we observe and report.

Occasionally, what we are seeing could be a matter of life and death. We have to make a decision, sometimes split-second, on whether it’s more important to report on the news, or whether we can offer assistance and help save lives.

It might be possible to do both, but sometimes the journalist becomes part of the story, making reporting difficult. In those cases their news priorities might have to come second.

Of course, each case has to be judged on its merits. In this particular case the reporter decided that his immediate job was to assisted fans and later paramedics in the rescue operation (and got hit with batons by police who misunderstood his motives).

He knew that his colleagues in the commentary box would be able to report on the unfolding scenes below them (which they did), and that the newsdesk would be supplied with updates – if not the first-hand experiences he was going through.

He was aware that the nearest telephone box was about 800m away but that riot police were already blocking the exits and that it wouldn’t be easy to get to a phone to file a report.

And he also knew that he might get reprimanded for not finding a way to file a live report about what was happening. But in that moment he had to decide.

He was still able to file a report three hours later about what he had witnessed that day (the only eye-witness account of what happened on the terraces to be broadcast), and he was still able to complete his documentary.

But he wasn’t first with the news, despite being the closest journalist to the tragedy that was unfolding.

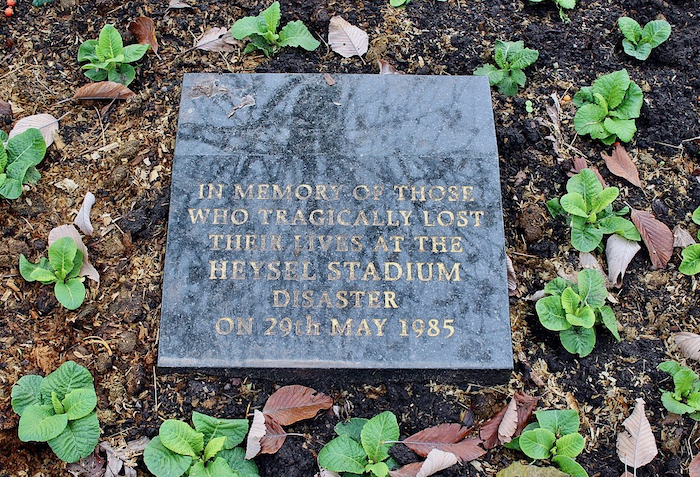

Sadly, 39 people died that day; 600 were injured, including the reporter.

Reaction

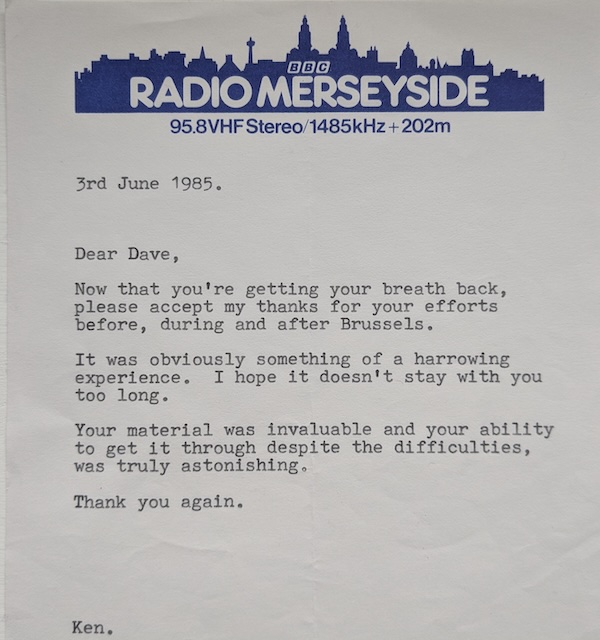

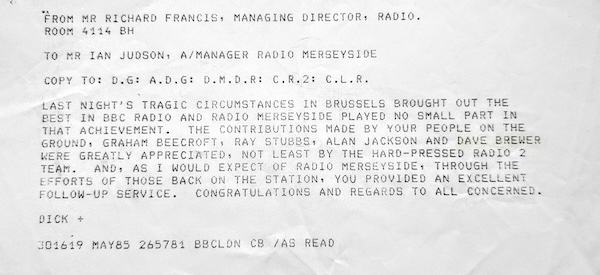

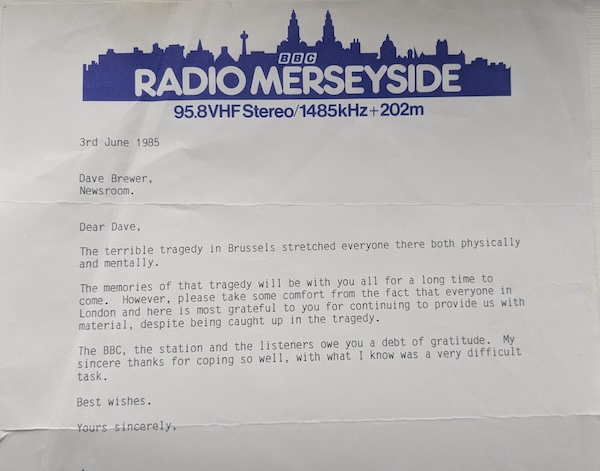

In the scenario set out above, the reporter’s actions were appreciated by his managers both locally and nationally. Not once was he reprimanded for his failure to update the newsdesk.

Three messages of support are embedded below.

These are important, and a reminder for today’s senior editorial managers, because they show that those who manage the news understand the decisions reporters have to make, and the issues they often face, during the course of their newsgathering.

The text above presents a real-life scenario where a radio journalist covering a 1985 European Cup final finds himself witnessing a deadly stadium disaster. He must decide whether to prioritise reporting the unfolding tragedy or assisting in rescue efforts. The text highlights the ethical dilemma faced by journalists in such situations, emphasising the importance of human life over the immediate pursuit of a story. It also underscores the crucial role of editorial managers in supporting journalists who make difficult decisions in traumatic circumstances.

Analysis:

- Ethical dilemma:

- The core of the scenario is the conflict between a journalist’s duty to report and their moral obligation to help those in need. This is a classic ethical dilemma that journalists face in various contexts.

- The text correctly points out that sometimes, “the journalist becomes part of the story,” blurring the lines between observer and participant.

- Context of 1985:

- The 1985 setting is crucial. The lack of mobile phones and instant communication tools significantly impacted the journalist’s ability to report quickly. This highlights how technological advancements have changed the landscape of news reporting.

- The condition of the stadium, and the police actions are also important to note, and are very much a product of that era.

- Importance of editorial support:

- The text emphasises the significance of supportive editorial management. The positive reactions from the journalist’s managers demonstrate the importance of understanding and empathy in news organisations.

- This is a very important point, as reporters that work in traumatic situations can suffer from PTSD, and other mental health issues.

- Humanity vs. “the scoop”:

- The journalist’s decision to prioritise helping over immediate reporting underscores the value of human life. It serves as a reminder that “getting the scoop” should never come at the expense of ethical considerations.

- The fact that he was still able to file a report later, and to finish his documentary, shows that doing the right thing, does not always mean losing the story.

- The impact of trauma:

- The text briefly mentions the journalist being injured. However, it’s essential to acknowledge the potential for psychological trauma in such situations. Journalists who witness traumatic events can experience PTSD, anxiety, and other mental health issues.

- News organisations have a responsibility to provide support and resources to journalists who work in dangerous or traumatic environments.

- The evolving role of journalism:

- In the age of social media and citizen journalism, the lines between observer and reporter are increasingly blurred. This scenario raises questions about the evolving role of journalists and their responsibilities in a digital age.

- With the rise of “fake news” the importance of professional journalists, that are able to report accurately, clearly, and ethically is more important than ever.

- Lessons for modern newsrooms:

- This scenario offers valuable lessons for modern newsrooms. It highlights the need for clear ethical guidelines, comprehensive training, and robust support systems for journalists.

- It is also a reminder that news managers should value the human element of journalism and prioritise the well-being of their staff.

- The importance of eye witness accounts:

- The fact that the reporter was the only eye witness to give a account of what happened on the terraces, shows the importance of having reporters on the ground.

In essence, this text serves as a powerful reminder that journalism is not just about reporting facts; it’s about upholding ethical principles and recognising the humanity of those involved in the stories we tell.