Proactive journalism is an approach to newsgathering where reporters take the initiative in seeking out stories rather than relying on wires feeds.

Traditional journalism often involves reacting to news releases, press conferences, and breaking events.

Proactive journalism is a deliberate, investigative approach that empowers journalists to anticipate, explore, and expose stories of significant public interest. It’s about setting the agenda, not just following it.

Proactive journalism

Shaping the narrative

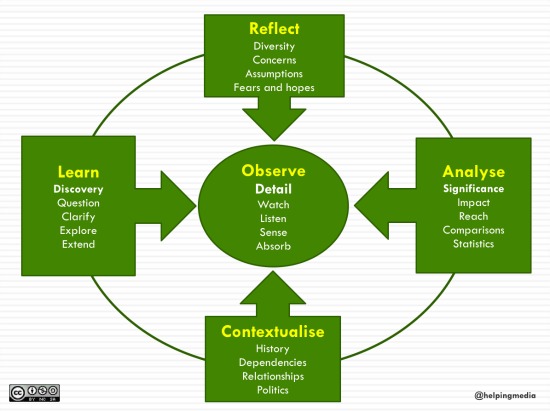

This proactive approach is characterised by a commitment to uncovering hidden truths and holding power accountable through a structured, multi-stage process:

- Observing and questioning:

- This goes beyond surface-level reporting. It’s about critically examining every piece of information, even seemingly straightforward press releases or speeches.

- Proactive journalists actively challenge assumptions, seek diverse perspectives, and rigorously test claims with independent data.

- They understand that every source has a potential bias and strive to present a balanced and comprehensive view.

- The goal is to move beyond simply relaying information to understanding the underlying dynamics and potential conflicts of interest.

- Learning and investigating:

- This stage involves in-depth research to validate information, clarify ambiguities, and identify knowledge gaps.

- Proactive journalists pursue clarity, refusing to report on anything they don’t fully understand.

- They seek to uncover new angles and perspectives, transforming complex issues into accessible and engaging narratives.

- They are dedicated to finding the truth, and following that truth where ever it may lead.

- Analysing and deducting:

- This involves systematically organising and evaluating all collected information, including observations, research, and source materials.

- Proactive journalists assess the potential impact and reach of a story, considering the diverse stakeholders and long-term implications.

- They connect the dots, identify patterns, and draw informed conclusions based on the evidence.

- Reflecting and collaborating:

- This is a crucial step for ensuring accuracy, fairness, and objectivity.

- Proactive journalists seek feedback from editors and colleagues to challenge their own assumptions and identify potential biases.

- They prioritise editorial integrity, ensuring that all significant voices are represented and that the story is presented in a balanced and responsible manner.

- This is where the strength of the story is judged.

- Contextualising and illuminating:

- This involves providing the audience with the necessary context to understand the significance of the story.

- Proactive journalists delve into the history of the issue, explore relevant trends, and identify broader connections to political, social, and economic factors.

- They are looking for the “why” of the story.

- They seek to uncover patterns, make comparisons, and reveal the underlying forces that shape events.

- They find the real story.

By embracing these principles, proactive journalism empowers citizens to make informed decisions and hold powerful institutions accountable. It fosters a more informed and engaged public, contributing to a healthier and more transparent society.