Asking the questions that need to be asked

In a previous module we looked at the topic of proactive journalism, where journalists are encouraged to observe, learn, reflect, analyse, and add context when producing news stories. In this module we look at story development.

This module is about thinking of the related stories, angles, or missing pieces of the story that can be produced in order to help explain the main story and enhance the audience understanding of the issue being covered.

For this exercise we consider a recurring story in Vietnam – flooding – and we look at the various angles that could be followed up. First we have the main story.

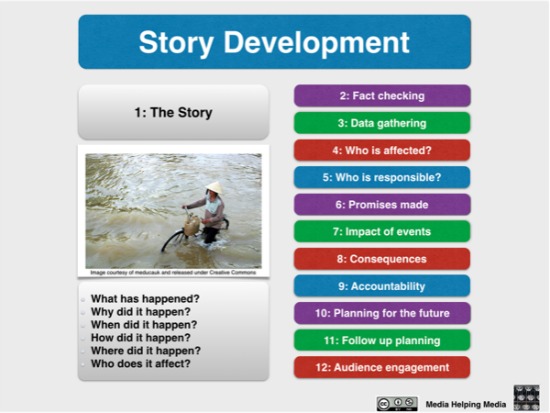

1: The story

This is fairly straightforward. We just need to ask the basic journalistic questions of what, why, when, how, where and who. So, in creating the main story we need to ask:

- What has happened?

- Why did it happen?

- When did it happen?

- How did it happen?

- Where did it happen?

- Who does it affect?

Asking these question should give us the main story and headline.

But responsible reporting that aims to inform the public debate with robust investigative journalism needs to go further. Let’s look at what we have to work on from the main story.

2: The facts

Now we can start to expand the story using the story development model. We need to start to piece together the facts, or the evidence. And these so-called ‘facts’ need to be examined, tested and proven to be accurate by confirming with at least two independent sources.

- What do we know?

- Is our information accurate?

- What is the source?

- Why are they sharing?

- What facts could be missing?

- What don’t we know?

- Who should we talk to?

- Why are they important?

- What could be hidden?

- Who is doing the hiding?

By this stage we will have built up a story plan which, when we discuss with our news team, will produce several ideas for follow up angles (related stories).

What we are able to piece together at this point are the following:

- Flooding fact file – a list of bullet points.

- Flooding maps – where the flooding happened.

- Flooding profiles – background information on the area most affected.

Having gathered some facts we now need to look at the data used to support the evidence.

3: The data

- What is the source of the data?

- Is it reliable?

- Can you verify?

- Check with officials, NGOs, campaigners, academics.

- Seek out regional comparisons regarding flooding in other provinces, regions, neighbouring countries.

- Find out what is the history of flooding in the area?

- Check whether any projections were made in the past that could have reduced the impact?

At this stage something interesting is starting to happen. As we dig deeper, new story angles are emerging.

Let’s consider just a few that might be inspired by point three.

- The flooding: campaigners warn that it could happen again.

- The flooding: comparisons between regions – how others are coping.

- The flooding: officials say relief and aid will arrive in time.

Now we need to get first-hand experiences to illustrate the story.

Of course we will have some personal experiences in the main story, but once we establish what has happened, and understand the scale compared to previous floods, we can now ask more intelligent questions when talking to the victims.

4: Who is affected?

- What is their story?

- Before the incident, during the incident, after the incident.

- Who do they care for and who still needs help?

- Who can’t get help?

- What help is offered?

At this point we will have a series of personal accounts of the flooding.

- The flooding: the victims tell their stories.

- The flooding: the annual disaster that has become a way of life.

- The flooding: the communities still stranded and in need of help.

Having spoken to people affected by the flooding we can now look at who is responsible, and what was the cause.

5: Responsibility

- Who or what was responsible?

- What went wrong?

- Why did it go wrong?

- Were all possible preventative measures taken?

- What are the authorities doing?

- Will it happen again?

- If not, why not?

- If it will, what can be done?

This should produce some fairly straightforward angles for story follow up, including:

- The flooding: Who was to blame? Officials, NGOs and campaigners point the finger.

- The flooding: Authorities say preventative measures planned.

- The flooding: Did local communities ignore warnings?

Having attempted to establish responsibility, we can also look at promises made in the past.

6: The promises

- In the present and in the past.

- Preventative measures promised.

- Local authority plans.

- Aid and relief offered.

- Infrastructure changes suggested after the last floods.

- Tackling the causes, deforestation, dams etc.

- Compensation offered to those affected last time.

- What fact-finding was carried out and what was done with the information.

Suggested follow up angles from the above include:

- The flooding: learning from the lessons of the past.

- The flooding: why preventative measures failed.

- The flooding: did the aid get through to those in need?

This is the stage where our archive becomes valuable.

We will have material from previous coverage of the flooding. We need to include this in order to provide context. Please refer to the other training module in this series about “Proactive journalism”.

All the above helps us assess the scale of the problem and try to establish an accurate view of the impact.

7: The impact

- Now and in the future.

- On crops and the general economy.

- The environment and whether it can recover.

- Health issues related to contaminated water, lack of medicine etc.

- Infrastructure, roads, railways, communications.

- Communities cut off.

- Families separated, unable to contact one another.

- Individuals missing, injured, bereaved.

Some story ideas resulting from the above considerations could include:

- The flooding: the economic impact on the environment.

- The flooding: the cost of repairing the infrastructure.

- The flooding: the impact on remote rural communities.

As the picture builds we are in a better position to view the consequences.

8: The consequences

- A complete solution, part solution, or no solution.

- Aid gets though, part aid gets through, or no aid gets through.

- Changes in lifestyle for some and what happens to those who can’t change.

- The economic future for all.

Such considerations could mean related stories being produced about:

- The flooding: prevention plans for future years.

- The flooding: the true cost of getting aid to those in need.

- The flooding: lifestyle changes required to cope with annual disaster.

As we continue to develop angles, dig deep and explore the topic we will start to develop some ideas of who might be accountable.

9: Accountability

- Who knew?

- What action was taken?

- Was it too early or late?

- Who is to blame?

- What local authority action was taken?

- Were there warnings given?

- Did the warnings reach those in danger?

- Were the warnings heeded?

- If not, why not?

- Is there any suspicion of any corruption?

The considerations above could lead to more related stories such as:

- The flooding: was enough done to prepare communities?

- The flooding: were warnings ignored and, if so, why?

- The flooding: the hidden factors that increased the likelihood of a disaster.

The question of corruption will come up as we start to assess accountability. We then need to look to the future.

10: The future

- What is the plan?

- What are the options?

- Who will it involve?

- What are the changes?

- Will they be phased?

- Is any adjustment needed?

- Is any training needed?

- What are the contingency plans?

- Is any education needed?

- What are the community plans?

This list provides us with several related story ideas, including:

- The flooding: future plans to prevent another disaster.

- The flooding: campaign to educate those living under the risk of floods.

- The flooding: community relocation plans to rehouse those at most risk.

Already we will probably have thought up 10 different angles on the flooding story with at least three related stories for each angle.

At this stage we should have at least 30 original story ideas that attempt to explain the complexity of the issue we are covering on behalf of our audience.

This is story development. This is in-depth, robust, responsible journalism aimed at fully informing the public debate. But all this material needs managing.

This task might be taken on by the planning editor. In an earlier module we discussed the role of the planning editor and his/her team. They will need to ensure the story is followed up.

11: The follow up

- Set a follow up date.

- Three or six months.

- List questions to ask.

- Note promises/targets.

- Check timetables.

- Keep archive.

- Revisit victims.

- Check with authorities.

- Interview experts.

- Arrange studio debates.

Of course the planning role will also produce new story opportunities, such as:

- The flooding: six months / a year on – what has changed?

- The flooding: from our archive – a special report on communities under water.

- The flooding: studio debate – the experts meet the public face-to-face.

And while all this is going on there will be a need to engage the audience in debate via the social media platforms used by victims, aid agencies, authorities, concerned relatives, and general public.

12: Engaging the audience

- Discuss on Facebook.

- Use other social media.

- Ask for experiences.

- Interview people.

- Stimulate debate.

- Ask questions.

- Offer answers.

- Publish fact files.

- Publish maps.

- Offer help and support.

And this part will also produce related stories, including:

- The flooding: How social media responded.

- The flooding: Your pictures of the disaster.

- The flooding: Interactive maps and timelines for you to share.

An example to apply to all big stories

The methods outlined above can’t be applied to every story; newsrooms don’t have the resources for that. However, such treatment should be considered for big, recurring stories or events where there is significant local impact, and where there is likely to be a growing archive of previously-prepared material.

To help us decide what stories deserve such detailed story development we can use two tools that are shared on this site. One is the “content value matrix”, and the other is the “story weighting system”.

Both are designed to help media managers and journalists focus resources on the stories that are of most value to the target audience.