Journalism is about far more than simply gathering information then passing it on. An essential part of the editorial process is to examine everything we are told to make sure it is factual.

We then add context so that any facts that are uncovered are considered alongside existing knowledge.

This is the first of two articles on this site about fact-checking. The other is ‘Beyond basic fact-checking‘ which we recommend you read after finishing this piece.

Journalists have a responsibility to apply editorial values to every piece of information that comes our way before we pass it on to others (see the material in our ethics section).

Once a piece of journalism is in the public domain it will be referenced, quoted, and possibly plagiarised as it becomes part of the global conversation. If that piece of journalism is untrue or flawed in any way, then lasting damage will have been done.

But let’s first agree what is meant by the word ‘fact’.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a fact is something that is “known or proved to be true”. It is also “information used as evidence or as part of a report or news article”. In legal terms, a fact is “the truth about events as opposed to interpretation”.

And that last definition is interesting, because journalists ‘interpret’ events by adding context – but more on that later. For now, let’s refer to facts that have not yet been fully tested as ‘claims’.

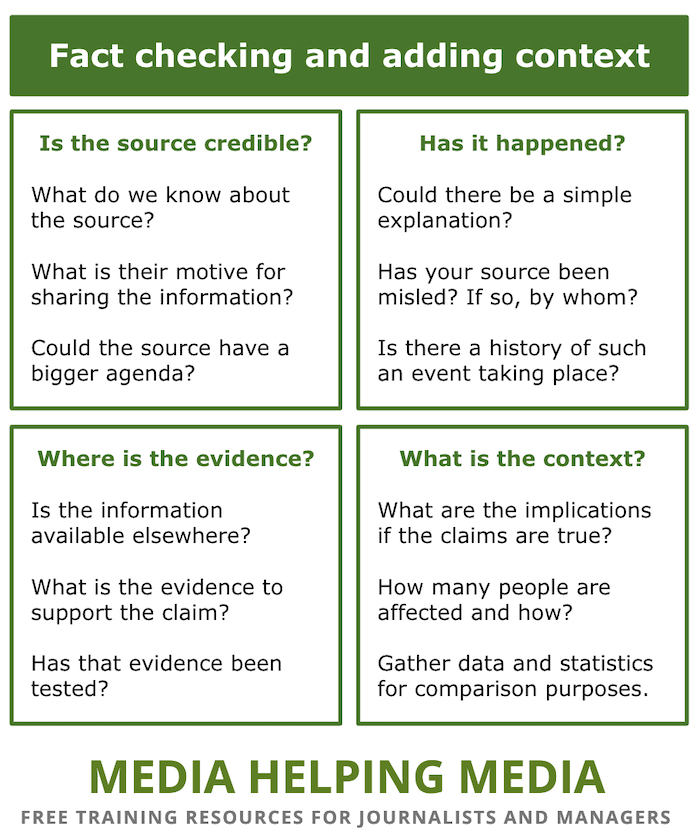

Here are a few tests that should be applied to information that a journalist receives from someone who ‘claims’ that what they are passing on is factual.

The first three tests are about source verification and fact-checking, the fourth is about adding context.

Is the source credible?

- What do we know about the source?

- What is their motive for sharing the information?

- Could the source have an agenda about which we are not aware?

Recommended: Research the background of the source, their connections, any previous record of sharing information.

Has it happened?

- Could there be a simple explanation?

- Has your source been misled? If so, by whom?

- Is there a history of such an event taking place?

Recommended: Research the chronology of events. Check your own news organisation’s archive. Search the web.

Where is the evidence?

- Is the information available elsewhere?

- What is the evidence to support the claim?

- Has that evidence been tested?

Recommended: Seek out a second, independent and trusted source.

What is the context?

- What are the implications if the claims are true?

- How many people are affected and how?

- Gather data and statistics for comparison purposes.

Recommended: Paint the bigger picture, understand the importance of the event in relation to other news stories.

Examples of adding context

- Economic context: When reporting on rising unemployment rates, provide context by including historical unemployment data, comparisons to other countries, and expert analysis on the economic factors contributing to the trend. For example, ‘While the current unemployment rate is 6%, this is a 2% increase from the previous quarter and the highest rate seen since the 2008 financial crisis.’

- Political context: When covering a new policy announcement, explain the policy’s history, its potential impact on different groups, and the political motivations behind it. For example, ‘This new environmental regulation is the latest in a series of measures aimed at reducing carbon emissions, following years of lobbying from environmental groups and facing opposition from industry leaders.’

- Social context: When reporting on a crime, provide context by discussing the social and economic factors that may have contributed to it, without excusing criminal behaviour. For example, ‘This incident occurred in an area with high rates of poverty and limited access to social services, which experts say can contribute to increased crime rates.’

- Historical context: When covering a protest, give the background of the reasons for the protest, any past protests concerning similar issues, and any key players in the organisation of the protest.

Those of you who are new to journalism might want to print out the following checklist and put it on the wall in your newsroom as a reminder.

If the results of your research make you feel uneasy you might want to drop the story. However, even a false claim, presented as fact, but, on investigation, found to be untrue, could still be a story. It could point to a political, commercial, or social conflict that might require investigation.

Never rule out a possible news story because the initial evidence presented proves to be shaky.

Now let’s look at point four ‘the context’ more closely.

Adding context

One dictionary definition of ‘context’ is: “the circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood.”

That word, ‘understood’, is important.

The role of a journalist is to enhance understanding. We do that by surrounding proven facts with data, statistics, history, and circumstances that, together, help paint a fuller picture of what has happened.

Think of it this way.

Imagine you are at home watching a series on TV. It’s the final episode of six. Just as the programme is reaching the conclusion there is a knock at the door. It’s a friend you haven’t seen for some time. You welcome them in.

As they walk through the door there is a scream from the lounge. One of the characters in the TV series has discovered the gruesome remains of a body. Your guest is shocked, but fascinated.

You offer to turn the TV off so you can chat, but they are so intrigued by what they saw on the screen that they ask you whether they could watch the programme with you, particularly as it’s reaching its conclusion. They want to know what happens next.

So you pause the programme, put the kettle on, make a cup of tea, and tell your guest about what has happened so far.

You explain who the characters are, what has taken place in previous episodes, how the situation has developed, the relationships between the characters, what clues you have picked up along the way, and how the plot has thickened to reach the point where your guest heard the scream.

And explaining the background proves to be important because your friend thought you must be watching a murder mystery, when, in fact, the series you were watching was a documentary about archeology. The scream was from an archeologist who had unexpectedly found mummified remains. It was not a modern-day crime thriller.

Now your guest has the context, so you can watch the end of the final episode together, with your guest informed about the background to the story and better able to understand events.

The same is true with journalism.

A colleague who was working as an intake editor on a news desk remembers receiving a call from an off-duty reporter who had just passed an overturned red double decker bus on a London street. People were wandering around with blood pouring from wounds. Two camera crews were mobilised, but before they’d even left the building the reporter discovered that it was a film crew making a movie. The story had changed once the reporter had checked his facts and explored the context.

I made a similar mistake when reporting on a fire at an inner city block of flats in Liverpool. I reported live into the 4pm news bulletin saying that residents were trying to salvage what they could from their burning homes. I was wrong. Had I checked my facts, not made assumptions, and taken time to establish the context of events I would have discovered that I was witnessing rioting and looting. You can read about that experience and the lessons learnt here.

The challenge all journalists face is not just to report the news but to also set out the background to an event as well as all related events in order to help the audience understand the elements of a story which they might otherwise find hard to comprehend – or even reach the wrong conclusion.

Perhaps it involves researching and setting out the chronology of events that have led to the current breaking news story. These can be presented as related stories.

You might need to research the backgrounds of the characters involved as you look for any social connections to anyone else involved. These can be presented as profiles.

Essentially, what you are doing is gathering as much information as possible in order to put together the most detailed, in-depth, and informative account of what has happened.

All this illustrates that journalism helps people make sense of the world – not just what’s happening, but why it’s happening. Stories that raise questions without even attempting to address those questions are weak stories.

- A bridge has collapsed. Why?

- A racing driver stops his car while leading the race. Why?

- A politician resigns. Why?

A news story without context can never be completely understood. A news source that is not verified can never be completely trusted. A claim, left unchecked, might not necessarily be a fact. And a news story without fact-checking and context could add more to the cacophony of confusion than to the enhancement of understanding.

The evolving nature of truth

Beyond revisiting and revising, it’s important to acknowledge that “truth” itself can be complex and contested, particularly in stories involving social issues or conflicting narratives.

Fact-checking isn’t just about verifying isolated facts; it’s about understanding the different interpretations of those facts and how they contribute to larger narratives.

Journalists should strive for accuracy and fairness, acknowledging where interpretations diverge and avoiding presenting a single, definitive “truth” when it doesn’t exist.

Examples

- In reporting on a controversial trial, present the prosecution’s and defences arguments fairly, even if they contradict each other. Clearly label each perspective and avoid presenting one as the definitive truth. For example, ‘The prosecution argued that the defendant acted with malice, citing X evidence, while the defence maintained that the defendant acted in defence, citing Y evidence.’

- When covering a historical event with multiple interpretations, acknowledge those differing interpretations and provide sources for each. For example, ‘Historians disagree on the exact causes of the civil war, with some emphasising economic factors and others focusing on social tensions. Both perspectives are supported by historical evidence, as seen in the works of [source 1] and [source 2].’

- When reporting on a scientific study that has conflicting results from other studies, make the audience aware of those conflicts, and if possible give reasons for the conflicts.

Source evaluation in the digital age

Lateral reading is crucial, but so is understanding the motivations and potential biases of sources, especially online. Lateral reading is a technique for evaluating online information by opening multiple tabs in your browser to investigate the credibility of the source, rather than just reading the information on the page itself (which is called ‘vertical reading’).

- Is the source trying to sell something?

- Do they have a political agenda?

- Are they affiliated with a particular group or organisation?

These questions should be part of the fact-checking process.

We should also consider the rise of synthetic media (deepfakes) and the challenges they pose to verifying information.

Examples

- When encountering a website claiming to have groundbreaking scientific findings, use lateral reading by checking reputable scientific journals and organisations to see if those findings are corroborated. For example, searching for the study’s author or institution on Google Scholar.

- To verify the authenticity of an image, use a reverse image search tool such as Google Images or TinEye to see if the image has appeared elsewhere online and in what context. This can help identify manipulated or misattributed images.

- When a source quotes statistics, check the original source of those statistics. For example, if a source cites a statistic about poverty rates, look for the original report from a government agency or reputable research institution.

- Use tools such as whois to check who owns a website, and when it was created. This can help to determine the validity of the website.

Fact-checking as a collaborative process

Fact-checking shouldn’t be solely the responsibility of individual journalists. Newsrooms should foster a culture of fact-checking, where everyone is encouraged to question and verify information.

This can involve dedicated fact-checking teams, collaborative editing processes, and clear guidelines for source evaluation.

The limits of fact-checking: Fact-checking can verify specific claims, but it can’t always address broader issues of interpretation or framing.

A story can be factually accurate but still misleading if it’s presented in a way that distorts the overall picture. This highlights the importance of context.

Examples

- Always verify the date of information, especially in rapidly evolving situations. Outdated information can be misleading. For example, a study from 2010 on climate change may not reflect the latest scientific consensus.

- Consider the ongoing validity of information. A source that was credible in the past may have changed its stance or credibility over time. For example, a political organisation’s website may have been updated with new, potentially biased, information.

- When using archive material, always make the date of the material clear to the audience. For example, ‘In a 1960 news report…’

Deepening the discussion of context

Context and power: Context is not neutral. Those in positions of power often have greater control over the narrative and can shape the context in ways that benefit them.

Journalists should be aware of these power dynamics and strive to provide context that challenges dominant narratives and gives voice to marginalised perspectives.

The “how” question: In addition to “why,” exploring the “how” is crucial. How did this event happen? What were the processes and mechanisms involved?

Understanding the “how” can reveal systemic issues and prevent similar events from occurring in the future.

Context and time: Context is not static; it evolves over time. A story that is accurate and contextualised today might be incomplete or misleading tomorrow as new information emerges.

Journalists need to be prepared to update their reporting and provide ongoing context as the story unfolds.

The ethics of context: Providing context can sometimes involve revealing sensitive information or information that could be harmful to individuals or groups.

Journalists must carefully weigh the public’s right to know against the potential harm and make ethical decisions about what context to include.

Adding perspective

The business model of misinformation: The spread of misinformation is often driven by economic incentives. Clickbait headlines, sensationalised stories, and emotionally charged content can generate more clicks and revenue, even if they are not accurate.

Understanding the business model of misinformation is crucial for combating it.

The role of technology platforms: Social media platforms and search engines play a significant role in the dissemination of information, both accurate and inaccurate.

Journalists should be aware of how these platforms work and how they can be used to spread misinformation.

They should also advocate for platform accountability and transparency.

The importance of media literacy education: Empowering the public with media literacy skills is essential for creating a more informed and engaged citizenry.

Media literacy education should be taught in schools and made available to people of all ages.

Journalism as a public service: At its best, journalism serves the public interest by providing accurate information, holding power accountable, and fostering informed debate.

By prioritising fact-checking and context, journalists can uphold these values and contribute to a more just and democratic society. We need to reinforce the idea that journalism is a vital public service, not just a business.

Questions

- What is the primary role of journalism according to the text?

- How does the author define a ‘fact’ in the context of journalism?

- What are the four tests mentioned in the text that should be applied to information received by journalists?

- Why is it important for journalists to add context to the facts they report?

- How does the text illustrate the importance of context with the example of the TV series?

- What mistake did the reporter make when reporting on the overturned bus, and what lesson does it teach about context?

- How does the text suggest journalists should handle claims that are found to be untrue?

- In what ways can journalists enhance the audience’s understanding of a news story?

- What is the significance of verifying news sources according to the text?

- How does the text differentiate between a claim and a fact?

Answers

- The primary role of journalism is to gather information, ensure it is factual, and add context to enhance understanding.

- A ‘fact’ is something known or proved to be true, used as evidence or part of a report, and distinct from interpretation.

- The four tests are: source credibility, occurrence verification, evidence availability, and context understanding.

- Adding context helps the audience fully understand the circumstances and implications of the facts reported.

- The TV series example shows how context changes the understanding of events, illustrating the importance of background information.

- The reporter mistook a film set for a real event, teaching the importance of verifying facts and understanding context.

- Even untrue claims can be stories if they reveal underlying conflicts or issues that require investigation.

- Journalists can enhance understanding by providing background, chronology, and profiles related to the news story.

- Verifying news sources is crucial to ensure trustworthiness and accuracy in reporting.

- A claim is an untested assertion, while a fact is verified and proven to be true.

Lesson plan for trainers

If you are a trainer of journalists we have a free lesson plan: Fact-checking and adding context which you are welcome to download and adapt for your own purposes.

If you found this helpful you might want to check our related training module ‘Beyond basic fact-checking‘.