Reporting on climate change presents journalists with major hurdles, as it’s a topical, controversial subject rooted in complex scientific research.

To meet these challenges, a journalist must rely on the editorial standards and ethics that are common to all good, public service reporting. The objective, as in all high-quality coverage, is to deliver well-informed, accurate, and unbiased reporting.

We have to be scrupulously correct in everything we write, explore all perspectives, gather information and evidence, check facts, understand the context, and then present the information we have to the audience clearly, impartially, and without any bias – then let the audience draw their own conclusions.

As an environment journalist covering climate change you will need to deal with complex scientific data as well as assessing the human impact of changing temperatures and weather patterns on individuals, communities, and ecosystems.

You will need to investigate and understand alternative views on why climate change is happening and, as with scientific evidence, weigh up their relevance to your story.

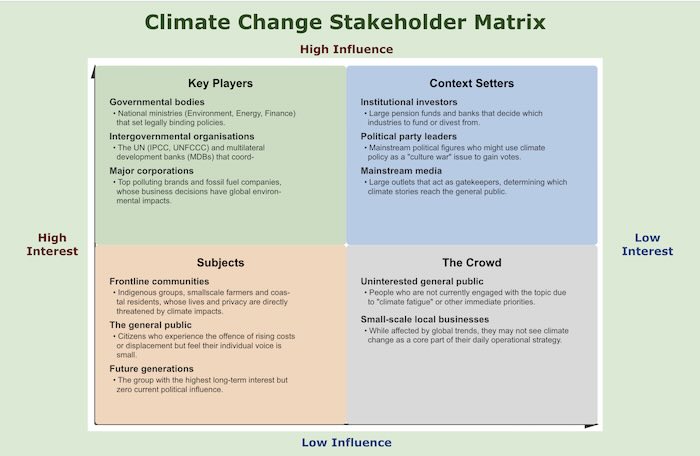

First let’s look at the stakeholders. Working out who has an interest in the topic of climate change is a crucial step for journalists. It helps them move beyond the science and understand the power dynamics that drive climate policy and public discourse.

The stakeholders matrix below categorises key actors based on their influence (their power to enact or block change) and their interest (how much they are affected by or invested in the outcome).

Global stakeholder matrix for climate reporting

1. Key players (high influence, high interest)

These are the actors who actively shape the climate landscape and must be the primary focus of investigative reporting.

- Governmental bodies: National ministries (Environment, Energy, Finance) that set legally binding policies.

- Intergovernmental organisations: The UN (IPCC, UNFCCC) and multilateral development banks (MDBs) that coordinate global action.

- Major corporations: Top polluting brands and fossil fuel companies whose business decisions have global environmental impacts.

- Climate activists: Groups like Greenpeace or Greta Thunberg who hold high public influence and drive media narratives.

2. Context setters (high influence, low interest)

These groups have the power to influence the climate agenda, but it may not be their primary goal or they may have conflicting priorities.

- Institutional investors: Large pension funds and banks that decide which industries to fund or divest from.

- Political party leaders: Mainstream political figures who might use climate policy as a culture war issue to gain votes.

- Mainstream media: Large outlets that act as gatekeepers, determining which climate stories reach the general public.

3. Subjects (low influence, high interest)

These are the groups most directly affected by climate change but often have the least power to change the policy.

- Frontline communities: Indigenous groups, small-scale farmers, and coastal residents whose lives and privacy are directly threatened by climate impacts.

- The general public: Citizens who experience rising costs or displacement but feel their individual voice is small.

- Future generations: The group with the highest long-term interest but zero current political influence.

4. The crowd (low influence, low interest)

These stakeholders are neither highly influential nor directly impacted in a way they currently recognise, but they are still part of the wider discourse.

- Uninterested general public: People who are not currently engaged with the topic due to being bored hearing about climate issues or other immediate priorities.

- Small-scale local businesses: While affected by global trends, they may not see climate change as a core part of their daily operational strategy.

Let’s see how all that information works in a matrix. The following graphic was produced by ChatGPT based on the content above. Journalists might want to create their own matrix with different information. The one below is just a suggestion.

How journalists use this matrix

By understanding the interests of the stakeholders a journalist can ensure fairness and accuracy by:

- Challenging the key players: Investigating if their public statements match their funding and integrity.

- Amplifying the subjects: Giving a voice to those with high interest but low influence, ensuring their stories are reported with accuracy.

- Identifying bias: Checking if the context setters are using their power to push a specific political or economic agenda.

Expertise

An environmental or science correspondent covering climate change will have to have a broad understanding of climate science or policy in order to interpret complex data and policy discussions.

Beyond formal education, proven experience as a journalist is essential, with a track record of reporting on complex issues. A demonstrated understanding of climate science, policy, and related fields is a must.

Experience in data journalism and multimedia storytelling can be a significant advantage, allowing for more engaging and impactful reporting.

You will also need to understand alternatives views – for example, as to why the weather is changing – and assess them as you compile your reports.

Communication

Excellent writing, communication, and presentation skills are essential. A climate change correspondent must be able to translate complex scientific and policy information into accessible language for a broad audience.

Strong research and analytical skills are crucial for investigating and reporting on the multifaceted aspects of climate change.

The ability to work both independently and collaboratively is also important, as these journalists often work with scientists, policymakers, and community leaders.

Guides

Some climate correspondents will be working as freelancers – meaning that they are not attached to any particular news organisation.

The European Journalism Centre (EJC) has published ‘A freelancer’s guide to reporting on climate change‘ which offers advice for freelancers reporting on climate change, highlighting the importance of their role in reaching a broader audience and influencing individuals and policymakers. Here’s a summary of the main points:

- Focus: Break down the broad topic by concentrating on specific areas such as activist groups from all sides of the issue, government actions, solutions, or climate adaptation.

- Precision: Be accurate when linking real-world events to climate change, and incorporate personal stories to engage audiences.

- Human impact: Explore the experiences of those affected by climate change, particularly vulnerable communities and Indigenous peoples, and consider including non-human perspectives.

- Relatability: Connect environmental issues to everyday events to make stories more relevant to the audience, and explore the intersections of climate change with other areas like food security, health, and income inequality.

- Critical approach: Challenge existing perceptions, question narratives, and highlight inconsistencies in climate coverage.

- Scientific understanding: Grasp the scientific basis of climate change, use data effectively, and employ clear language to explain technical details.

- Safety: Assess and prioritise safety risks when covering sensitive topics.

- Diversity: Include a wide range of interviewees, incorporate traditional and Indigenous knowledge, and avoid jargon to enhance accessibility and impact.

The final point about avoiding jargon is particularly important when explaining complex issues, as is understanding the frequently used words and terms that relate to climate change.

The organisation Covering Climate Now has produced a guide for journalists covering climate change as has World Weather Attribution which has produced an 18-page guide. Internews has produced a two-page pdf called ‘Covering Climate Change: A Journalist’s Guide to Science, Stories, and Solutions’.

Ethical journalism

Covering climate change demands a deep commitment to informing, educating, and explaining complex climate issues to a wide audience. A strong ethical compass and a dedication to journalistic integrity are essential. This includes a commitment to:

- Fact-checking: Ensuring the veracity of all reporting by applying robust fact-checking techniques as outlined in Fact-checking and adding context.

- Accuracy: Adhering to the highest standards of journalistic ethics and accuracy, as detailed in Integrity and journalism and Accuracy in journalism.

- Avoiding false balance and false equivalence: Ensuring that reporting reflects the scientific evidence on climate change and also includes, in proportion, alternative views, as explained in False equivalence and false balance.

- Recognising bias: Understanding and addressing the influence of conscious and unconscious bias in reporting and analysis, referencing Unconscious bias and its impact on journalism.

- Maintaining impartiality: Striving for impartiality in journalism, as explained in Impartiality in journalism.

- Dealing with disinformation and misinformation: Being equipped to handle the challenges of disinformation and misinformation, as outlined in Dealing with disinformation and misinformation.

- Using appropriate language: Presenting climate information in a manner that is understandable and relatable to a broad audience, using appropriate climate change tone and language.

- Employing correct terminology: Using the Climate Change Glossary from Media Helping Media to ensure accurate and consistent use of climate-related terms.

Commitment

Ultimately, the most effective correspondents possess a deep commitment to informing, educating, and empowering the public to make informed decisions and take action. Their work is characterised by integrity, accuracy, and a dedication to amplifying marginalised voices and holding policymakers accountable.

Related articles