Journalists should not waste words. Their writing should be concise and tight. Adjectives and adverbs clutter up news stories and should be avoided wherever possible.

When it comes to writing – not just news writing but any kind of writing – adjectives and adverbs have a bad reputation.

Mark Twain said: “When you catch an adjective, kill it.” Stephen King said: “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.”

For many decades, the conventional wisdom in journalism has been that you do not, usually, need adjectives and adverbs. Your sentences will be better if you cut them out.

But wait! I just used ‘usually’, an adverb, and ‘better’, an adjective. If I cut them out, the first sentence will no longer be accurate, since I am trying to say that there will, occasionally, be a need. And the second sentence does not work at all if I remove ‘better’.

So you cannot ban the use of adjectives and adverbs.

But you should keep them to a minimum. Mark Twain, in fact, modified his advice:

“I don’t mean utterly, but kill most of them (adjectives) – then the rest will be valuable.

They weaken when they are close together. They give strength when they are wide apart.

“An adjective habit, or a wordy, diffuse, flowery habit, once fastened upon a person, is as hard to get rid of as any other vice.”

Instead, make a virtue of economy: use as few words as possible.

The newspaper guru, Leslie Sellers, in his 1968 guide, ‘The simple subs book‘, put it this way: “fewer words, better sense”. Apply this across the board, but especially (a permissible use of the adverb in this case) with adjectives and adverbs.

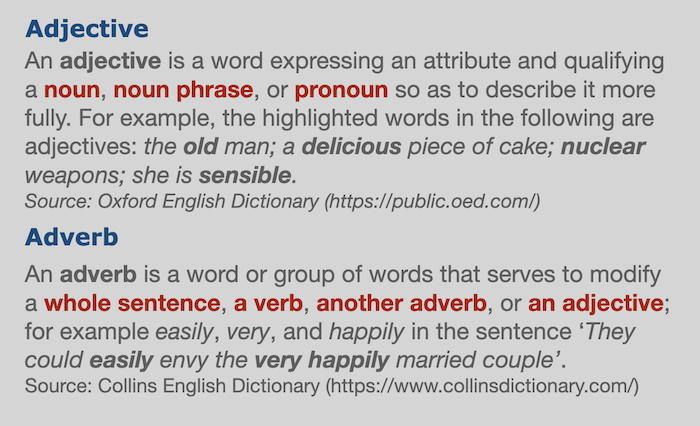

Adjectives and adverbs are words that modify. Adjectives change the meaning of nouns. Adverbs change the meaning of verbs, phrases, clauses or sentences. You should always test whether the modification is necessary.

Here are a few examples of commonly used but unnecessary modifiers, in which the first word can always be cut:

- completely untrue

- strictly necessary

- broad daylight

- considerable difficulty

- firm decision

- together with

- along with

- grateful thanks

- high-speed car chase

Adjectives to do with size are often too broad to add any useful meaning, like ‘big’, ‘huge’, ‘massive’, ‘astonishing’. They can be cut or replaced with something that adds to the understanding of the story.

Adjectives like ‘tragic’, ‘improved’, ‘sad”, “’incredible’, ‘unfortunate’ are especially dangerous since they include value-judgements. Leave it to your readers or listeners to make their own judgements.

Two of the most objectionable words are ‘really’ and ‘very’. They seldom add any meaning. Mark Twain suggested that every time you are tempted to write the word ‘very’ in your story, substitute the word ‘damn’ – then, as he put it, “your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be”.

Mark Twain was also down on adverbs. He said they were the tool of the ‘lazy writer’. In their most common form they end in ‘ly’ and are attached to verbs. Here are some sentences which would be better without their adverbs:

“She tiptoed silently into the room.”

“He glared aggressively at the traffic warden.”

“She knew perfectly well he was lying.”

“He completely rejected the allegation.”

In all these cases, the adverb states the obvious. The verb does the job without needing modification. Always try to let the verb stand alone – if it needs strengthening with an adverb, it is the wrong choice of verb.

Journalists choosing their words are the same as carpenters choosing a piece of wood or tailors choosing a length of cloth. We are all craftspeople and our success depends on using the right raw materials – in our case, words.

So be sparing in your use of adjectives and adverbs. It is one of the qualities that marks a professional.