Requirements for international media training

For international media training to be successful, tried, tested and proven case studies from a similar region are needed. Theory has limited value, as do examples of what works in the West, unless the examples directly relate to local issues and concerns.

You also need a great local co-trainer, management buy-in, enough time working one-to-one with participants, and a way of creating a solid network for future learning and development.

The following five tips are for those who want to ensure that what’s delivered is relevant, lasting and can be built on in the future.

1: Achieve buy-in from management

Training delivered following an external training needs assessment that focuses on superficial issues, such as poor TV packaging/presenting skills or sloppy writing, could be failing to identify the real issues that need attention.

Poor quality journalism and output are usually a reflection of an ailing media business.

The real issue may be at the heart of the organisation – the management. Helping them understand that certain changes could benefit their business is the best starting point.

If that process helps management understand the business reasons for the training, and they then buy into the process, then a proper training programme, focused on the business objectives, can be designed and delivered.

If that essential first step doesn’t take place the result could be disillusioned staff who finds there is no appetite from their line managers for them to apply the lessons taught to them on the course.

2: Deliver regionally-relevant case studies

Theory is never welcome on its own. People want case studies. Tried, tested, and proven examples of where the media business has improved through proper training implemented following the management buy-in (mentioned above), and which deliver results in terms of workflow efficiencies, audience satisfaction and increased revenue-generation.

They want examples which they can measure themselves against, practical steps that can yield results, and someone they can contact if they encounter problems.

Most of all, media organisations in the developing world appreciate examples from those who have delivered while dealing with similar issues to those they are facing.

Details of how things work at the BBC, CNN or Al Jazeera are all useful, but a media house in Africa may find tips and tricks from a media house in Asia more appropriate to their needs; in my experience they have certainly paid more attention to those examples.

3: Build local networks and associations

Media intervention is all about capacity building and transferring skills. It should also be about building local networks of like-minded individuals who can take that knowledge to the next level in a way that is culturally and regionally relevant.

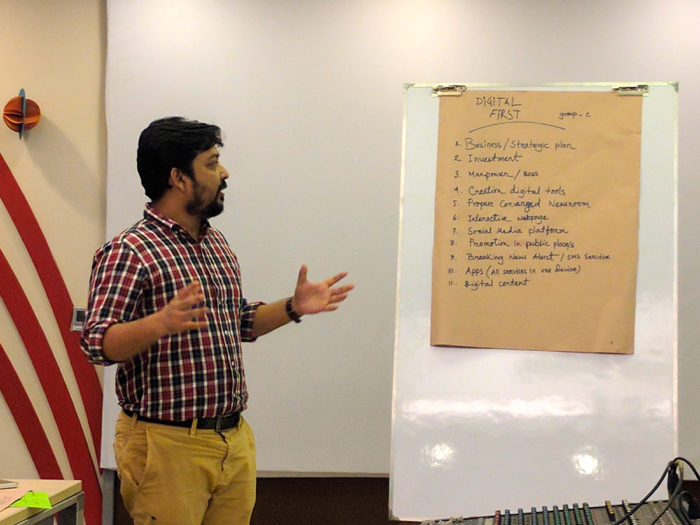

Usually, training course participants come from a selection of media organisations. Participants may already know each other, but may not have spent a work together working in interactive sessions and producing group presentations.

Finding how to build on those new relationships, in a way that enables further growth and development, is important. It could also lead to locally-organised training in the future run by those who benefited from the first training.

This capacity building should be a by-product of all interventions. The setting up of a local journalist association could help ensure that the fellowships created during the training are available for future generations.

4: Engage a local co-trainer

Flying in a Western ‘expert’ to deliver training is often welcome. Participants usually seem eager to learn from what is happening outside of their own regions. However, ensuring that training is relevant and sensitive to the local situation is crucial. Every intervention should be double-headed with the invited trainer working alongside a local co-trainer.

This is increasingly happening and, when it does, the training is enhanced.

The outside trainer and the local co-trainer need to spend enough time going through the proposed agenda, carrying out local research, ensuring all the presentations and group work is appropriate, and then sharing the task of delivering.

By the end of the week the international trainer needs to be working as the co-trainer to the local trainer. Ideally, the local co-trainer should run at least one session each day.

5: Offer one-to-one clinics

Feedback forms are important. It enables those organising the training to learn what participants thought about the benefits and flaws. However the feedback forms are often filled out in a rush at the end of a week of training when people are keen to get away and are probably not in the best frame of mind to offer a considered response.

Ideally, the invited trainer and the local trainer should schedule 20-minute clinics with each participants where they can talk through any issues that concern them and which they did not feel comfortable about raising in the group sessions.

These clinics are rather like going to see the doctor. The participant turns up with a question/issue, and the trainer and the co-trainer prescribe a course of action to deal with the problem. The trainers, both local and international, then make themselves available, via email, Skype, Facebook or Twitter to follow up with the participant, if needed (at no cost to the participant).

If there is a local association, the co-trainer could suggest the setting up of a self-help members-only forum where participants offer on-going support to their peer group and continue to learn together from locally-relevant experience.

The point is to ensure that all the effort that goes into organising training has a lasting benefit for those it was intended to help and that it was not just a box-ticking exercise.